"The unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics in the natural sciences is something bordering on the mysterious."

Abstract

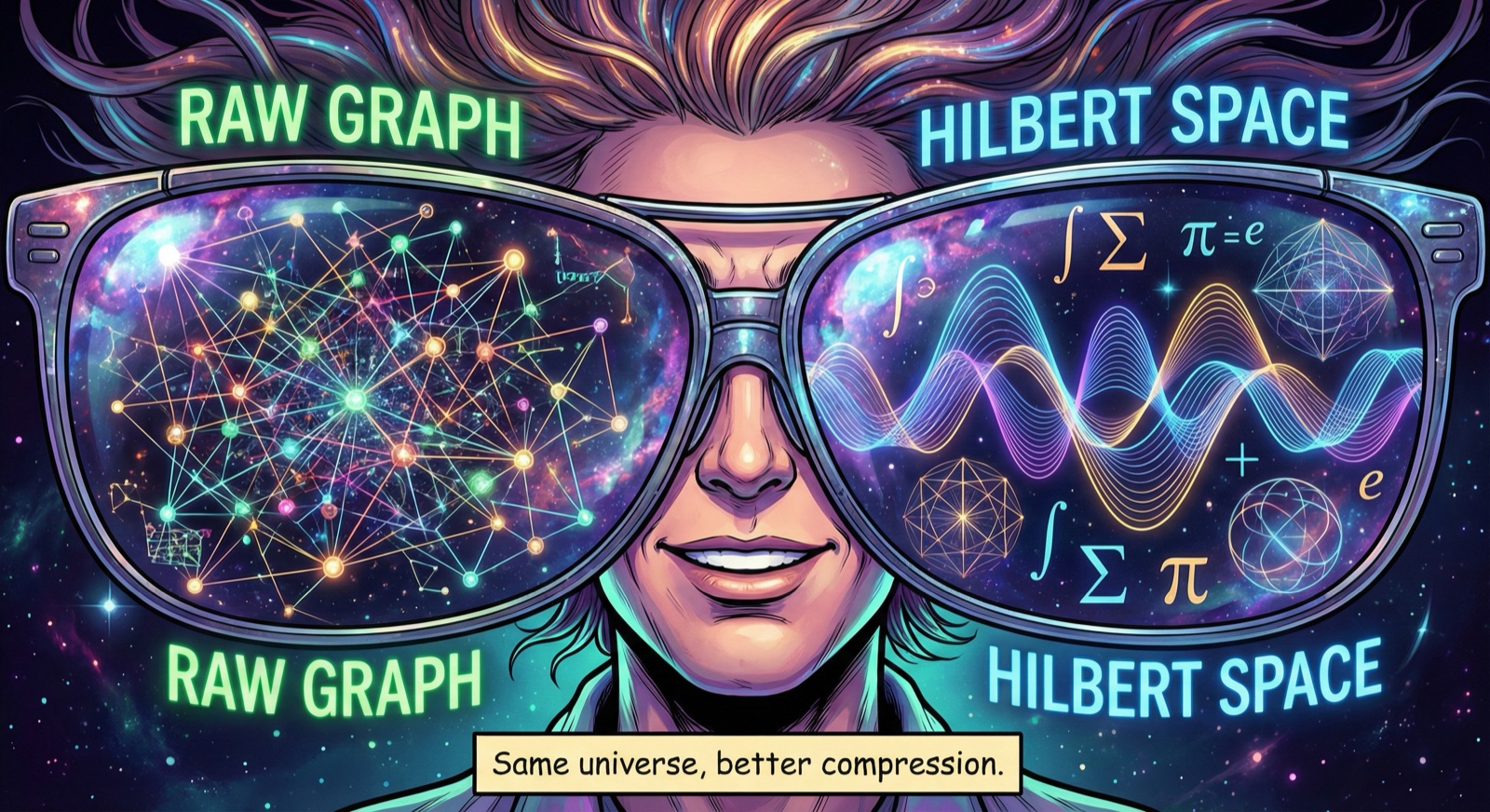

Why does quantum mechanics use infinite-dimensional Hilbert spaces — abstract vector spaces with complex coefficients — to describe physical reality? And why does it work so spectacularly well? The answer: Hilbert space is the linear algebra of vibrations on a giant network. It is not the "nature" of reality. It is the spectral approximation of a discrete graph. QM is the MP3 compression of the voxel universe.

This is the question that haunted Wigner: why should abstract mathematics — invented by humans for pure logical exploration — describe the physical universe with such uncanny precision?

In the framework of the Voxel Network, the mystery dissolves.

Hilbert space is not fundamental. It is emergent. It is the natural mathematical language that appears when you ask: "What are the resonant modes of an enormous discrete graph?"

I. The Laplacian Spectrum

In Framework C, the fundamental object is the Adjacency Matrix $A$ (or equivalently, the combinatorial Laplacian $L$) of the Universal Graph.

This is an immense matrix — roughly $10^{80} \times 10^{80}$ — discrete, sparse, and binary. Every entry is 0 or 1. Connected or not.

This matrix is incomprehensible to a human mind. We cannot visualize $10^{80}$ dimensions.

1.1 From Matrix to Music

But there's a trick. Instead of looking at the matrix directly, we ask: What are its vibration modes?

Every matrix has eigenvalues and eigenvectors. These are the "natural frequencies" and "standing wave patterns" of the network.

When you compute these eigenvectors, you pass from the discrete matrix to Spectral Geometry — the study of shapes through their vibration patterns.

Mathematical fact: When the number of nodes $N \to \infty$, the set of eigenvectors of a regular graph converges to... the orthonormal basis of a continuous Hilbert space.

The discrete becomes continuous in the limit. The matrix becomes an operator. The graph becomes a manifold.

Hilbert space is the statistical tool for describing the resonances of a network without computing each individual connection.

It is the "music" of the graph — the frequency decomposition of its vibrations.

II. Why Linearity?

Hilbert space is linear. This is the Superposition Principle:

Why should a complex network obey linear rules? Networks are usually messy, nonlinear, chaotic.

2.1 The Hooke's Law Regime

The answer is perturbation scale.

Large Perturbation

Pull a spring hard: it deforms strangely, breaks, behaves nonlinearly.

Small Perturbation

Pull a spring gently: deformation is perfectly proportional to force. Linear.

Particles (protons, electrons) are minuscule perturbations compared to the colossal tension of the vacuum (Planck energy $\sim 10^{19}$ GeV).

Since we operate in the regime of small perturbations, the network's response is perfectly linear.

Hilbert space describes this "elastic" regime of the vacuum — where the graph flexes gently without breaking its linear response.

This is why quantum mechanics is linear: not because reality is fundamentally linear, but because particles are tiny ripples on a vast, taut network.

III. The Inner Product

The magic of Hilbert space is the inner product $\langle \phi | \psi \rangle$. It lets you compute probabilities, measure angles between states, and define orthogonality.

On the voxel graph, this has a literal meaning:

$\langle \phi | \psi \rangle$ is the overlap coefficient — how many nodes the two vibration patterns share, weighted by amplitude.

$\langle \phi | \psi \rangle = 0$ (Orthogonal): The two vibrations use no common nodes, or their contributions cancel perfectly. They are topologically distinct.

$\langle \psi | \psi \rangle = 1$ (Normalized): The probability of finding the excitation somewhere on the graph is 100%.

Orthogonality in Hilbert space = topological distinctness on the graph. The inner product is counting shared nodes.

3.1 Probability from Geometry

The Born rule $P = |\langle \phi | \psi \rangle|^2$ now makes geometric sense:

Probability is not mystical. It's the geometric projection of one vibration pattern onto another.

IV. Where Hilbert Fails

This is where Framework C goes beyond standard physics.

Hilbert spaces work too well. They assume space is flat and infinite. They are mathematically perfect — and that's the problem.

Hilbert spaces cannot describe gravity (spacetime curvature) because curvature breaks the global linear symmetry of the vector space.

4.1 The Standard Approach

Standard physics tries to force gravity into a Hilbert space framework:

- Loop Quantum Gravity: Discretize spacetime, quantize the Hilbert space

- String Theory: Embed gravity in a larger Hilbert space (with extra dimensions)

Both approaches struggle. The infinities don't cancel. The predictions don't match.

4.2 The Framework C View

In our picture, the explanation is simple:

Hilbert space is only valid locally — in the tangent space at each point of the graph.

When information density ($6\pi^5$) becomes too high — near a proton, near a black hole — the network curves. The linear approximation (Hooke's Law) breaks down.

Gravity is what happens when Hilbert space saturates.

The reason we can't quantize gravity is that we're trying to use a linear tool (Hilbert space) to describe a nonlinear phenomenon (curvature). It's like trying to map a sphere with a flat piece of paper — it works locally, but globally you get distortions.

Quantum Mechanics works where the graph is flat.

General Relativity works where the graph curves.

Neither works alone where both effects matter.

V. The MP3 Analogy

Here's the summary in one analogy:

The Orchestra

The Voxel Graph

(Ontological reality)

$10^{80}$ nodes, discrete, binary

The MP3

Hilbert Space

(Mathematical description)

Continuous, infinite-dimensional

An MP3 file doesn't contain the orchestra. It contains a frequency decomposition of the sound waves — enough information to reconstruct the listening experience, but not the physical instruments.

Similarly, Hilbert space doesn't contain the graph. It contains a spectral decomposition of the graph's vibrations — enough to predict measurement outcomes, but not the underlying topology.

5.1 When MP3 Fails

MP3 compression works beautifully for most music. But if you crank the volume too high, or try to encode frequencies outside its range, you get distortion, clipping, artifacts.

Hilbert space has the same limitation. As long as the "music" (particle interactions) stays within normal ranges, the compression is indistinguishable from reality. But at extreme densities (black holes, Big Bang), the compression fails. You need access to the raw graph.

VI. Conclusion

Wigner's mystery is solved.

Mathematics is "unreasonably effective" because the mathematics we use (Hilbert space) is the natural spectral language of the discrete graph that underlies reality.

- Eigenvectors = vibration modes of the network

- Linearity = small perturbation regime (Hooke's Law)

- Inner product = node overlap on the graph

- Probability = geometric projection

We didn't invent Hilbert space and discover it matches reality. We discovered the resonances of reality and invented Hilbert space to describe them.

The universe is not written in the language of mathematics. The universe is a graph. Mathematics is just the most efficient way to describe its music without having to name every node.